Meet a really smart fellow named ANSELM 1043--1109 A.D.

He was elected ABBOT in Lombardy in 1078 A.D.

An ABBOT is the Father Superior in a monastery of monks.

Anselm was a smart cookie! His greatest asset was his intellect which he used to bring persons of Faith into an intellectual comprehension

of matters of belief without abandoning their rational thinking. Under his leadership the monastery became reknown as a center of learning.

In 1093 Anselm became the Archbishop of Canterbury in England at a time when the King, William Rufus, was confiscating revenue from the Cathedral for "royal use". This placed King and Church at odds, to say the least!

Anselm immediately got on the bad side of the king by visiting the Pope in Rome without the king's permission. Anselm was told he could not return! When William died in battle and Henry I took over the throne Anselm was allowed back.

Henry, like his predecessor William, was keen on having more control over the Church than the church had over him and his own authority.

Within 3 short years Anselm was in exile once more!

While in exile, Anselm began writing rather astounding works of intellectual vigor and religious

insight which would profoundly affect the world of faith in the Catholic religion.

What makes Anselm interesting to us today and to me in particular this fine September morning almost a thousand years later???

Just this, Anselm refused to abandon either his Faith or his Intellect. In the process of bringing these two polar opposites together under one roof he produced logical proof that God exists.

Anselm lived in a time of much debate. Anselm's private motto which he adopted in the manner of the time was:

fides quaerens intellectum :FAITH SEEKING UNDERSTANDING

Aselm did not seek to replace faith with knowledge. Rather, for Anselm, Faith was a Volitional state of willing oneself to be of the same mind as

God. Whereas the usual "person of faith" merely passively agreed to what things were heard and simply accepted them as true; Anselm

was of the strong opinion this invalidated one's WILL through no investigative process and meeting of intellectual rigor of inspection with that

acceptance.

"Faith that merely belieevs what it ought to believe is dead!" The mind must produce works (investigative and comprehending

examination) which validate the Faith BEFORE that believe is actively alive. So, for Anselm, "Faith without works is dead" means the unexamined

belief is without value to God. God needs the mind of man and not merely the actions of a puppet for satisfactory worship.

Oddly, for his time, Anselm had no use for the Supernatural (outside of nature) to explain God or Faith. Anselm in his own words:

If anyone does not know, either because he has not heard or because he does not believe, that there is one nature, supreme among all existing things, who alone is self-sufficient in his eternal happiness, who through his omnipotent goodness grants and brings it about that all other things exist or have any sort of well-being, and a great many other things that we must believe about God or his creation, I think he could at least convince himself of most of these things by reason alone, if he is even moderately intelligent.

Now that we understand where Anselm was coming from and where he stood on the matter of intellect and faith we can better appreciate how

drastically outside the box his Proof of God's existence really was in the 11th century.

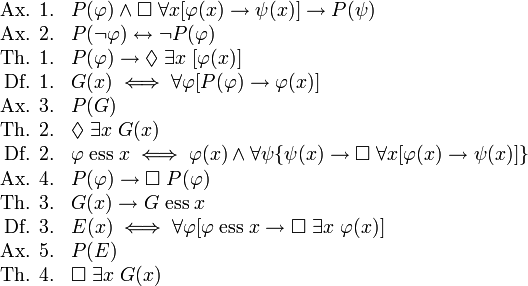

Here is ANSELM's argument. See how far you can go and agree with him and aske whether or not he succeeds.

1.In all existing things there must be a supremely good, almost as good, good and less than good among them.

2.Thus, all things are good in some degree. In that degree their goodness is derrived from the most supremely good among them.

Anselm continues:

So by the principle just stated, these things must be good through some one thing. Clearly that thing is itself a great good, since it is the source of the goodness of all other things. Moreover, that thing is good through itself; after all, if all good things are good through that thing, it follows trivially that that thing, being good, is good through itself. Things that are good through another (i.e., things whose goodness derives from something other than themselves) cannot be equal to or greater than the good thing that is good through itself, and so that which is good through itself is supremely good. Anselm concludes, “Now that which is supremely good is also supremely great. There is, therefore, some one thing that is supremely good and supremely great—in other words, supreme among all existing things”

Having created this foundation Anselm now delivers the knockout blow using reason alone:

Anselm argues that all existing things exist through some one thing. Every existing thing, he begins, exists either through something or through nothing. But of course nothing exists through nothing, so every existing thing exists through something. There is, then, either some one thing through which all existing things exist, or there is more than one such thing.

If there is more than one, either (i) they all exist through some one thing, or (ii) each of them exists through itself, or (iii) they exist through each other which makes no sense.

If (ii) is true, then “there is surely some one power or nature of self-existing that they have in order to exist through themselves” ; in that case, “all things exist more truly through that one thing than through the several things that cannot exist without that one thing” .

So (ii) collapses into (i), and there is some one thing through which all things exist. That one thing, of course, exists through itself, and so it is greater than all the other things. It is therefore “best and greatest and supreme among all existing things. ”

This is called Anselm's Ontological Argument. (Immanuel Kant called it that. In Anselm's day it was simply Anselm's proof.

God is “that than which nothing greater can be thought”; in other words, he is a being so great, so full of metaphysical oomph, that one cannot so much as conceive of a being who would be greater than God. The Psalmist, however, tells us that “The fool has said in his heart, ‘There is no God’ ” (Psalm 14:1; 53:1). Is it possible to convince the fool that he is wrong? It is. All we need is the characterization of God as “that than which nothing greater can be thought.” The fool does at least understand that definition. But whatever is understood exists in the understanding, just as the plan of a painting he has yet to execute already exists in the understanding of the painter. So that than which nothing greater can be thought exists in the understanding. But if it exists in the understanding, it must also exist in reality. For it is greater to exist in reality than to exist merely in the understanding. Therefore, if that than which nothing greater can be thought existed only in the understanding, it would be possible to think of something greater than it (namely, that same being existing in reality as well). It follows, then, that if that than which nothing greater can be thought existed only in the understanding, it would not be that than which nothing greater can be thought; and that, obviously, is a contradiction. So that than which nothing greater can be thought must exist in reality, not merely in the understanding.

What do you think of Anselm? His argument? Does it succeed? If so, why? If not, why not?

.jpg)